Coding with contracts - Components

Posted on in WebThis is the second in a series called ‘coding with contracts’, a look into writing robust API’s, components, and more!

Following on from the previous installment, we’re going to focus on component contracts.

Components require a similar level of trust to a REST API, in fact, we interact with them in surprisingly similar ways. A component exposes a public API, an I/O in the form of props and events. Keeping this API clear and consistent increases the trustworthiness of the component, making it easier to integrate.

A component developed in isolation within a pattern library will often face different challenges to one developed directly within a codebase. For these components, it’s especially important we document their I/O and declare how they can and should be used.

A component should lay out a considered API and stick to it. Tests should confirm that the I/O is unaltered after any refactoring.

Props

Props are the most common form of interaction with a component, and therefore one of the most crucial elements to tie down. They should be named logically, and declared with their accepted prop types. A developer integrating a component shouldn’t have to delve into the codebase to see how a prop works; it should be painfully obvious from the prop name, and followed up with a descriptive comment. There’s a great Storybook add-on for Vue, that’ll let you expose these descriptions.

“Good code is its own documentation” is a popular quip, most often used to explain or excuse a lack of comments. And although clarity at a micro scale (sensible variable names, logical arguments, good spacing) is important and may lead to fewer comments, I’m not sure a lack of documentation at a macro scale is such a good thing. A comment is perfect for explaining the whys and why nots. Finding out what a component doesn’t do is surprisingly useful, and often overlooked. This also a great place to get any UX and design considerations documented - new starters will find it invaluable to see the reasoning behind historic decisions.

Variants and inheritance

Components should be flexible, but not overstretch their reach. Flexibility shouldn’t just be handled by saturating the component with props. The more props, the more cognitive load required. Composing simpler, single responsibility components into more complex interfaces is a more scalable way of working.

An alternative approach is to make similar ‘variant components’. You’ll have more components in total, but they’ll be easier to digest and maintain, assuming you keep a consistent API with the simple component. This sounds like the place for a contract!

Mixins are definitely your friend here. They let you share common props, events, and methods with multiple components, keeping a tidy, single source of truth.

This approach isn’t unlike the programming principle of inheritance. A common example of classical inheritance is ‘animals’. Imagine a Dog class. It’ll contain unique methods/properties like woof() and .smell = wet, but it’ll also contain some more abstract methods like walk() and sleep(). These are common methods to all animals, so when we come to create a new Cat(), we have to copy & paste all the common code.

Inheritance means we can create an Animal base class, and create new animals by extension.

class Animal {}

class Dog extends Animal {}

class Cat extends Animal {}

All common methods live on the Animal, and unique methods on the variant. This not only keeps each class succinct and understandable, it also makes refactoring considerably simpler and less error prone.

The same concept can apply to components. If all ‘cards’ are extended from a base set of mixins, the common logic can be shared, leaving variants to handle only the unique logic. You might not even use a base card in the system, but it’ll act as a starting point for all other cards.

This also works for CSS as much as it does JS. An .animal class may only provide limited styling to common features, but when teamed with BEM, you’ve got a great starting point to create variants like .animal--dog.

Events

Where Props provide the input to a component, events provide the output. It’s the same execution model as HTML nodes: attributes are ‘input’ for the element, and event listeners tell us when things have changed, ie. output.

Vue does a wonderful job of separating these two concerns, exposing an ‘event emitter’ that you can use to fire events out of a child component. Calling this.$emit('click') in a child component sends it out to be picked up with an @click prop. Vue’s documentation on this is well worth a read.

React muddies these waters somewhat; you pass in an event listener function like any other prop, and call it directly in a child component. It’s more hands-on and perhaps more explicit, but there’s something wonderful about the opt-in event model in Vue. React’s never been one for separating concerns, and I wouldn’t be surprised if they work in very similar ways under the hood, but personally I like that distinction between component input and output.

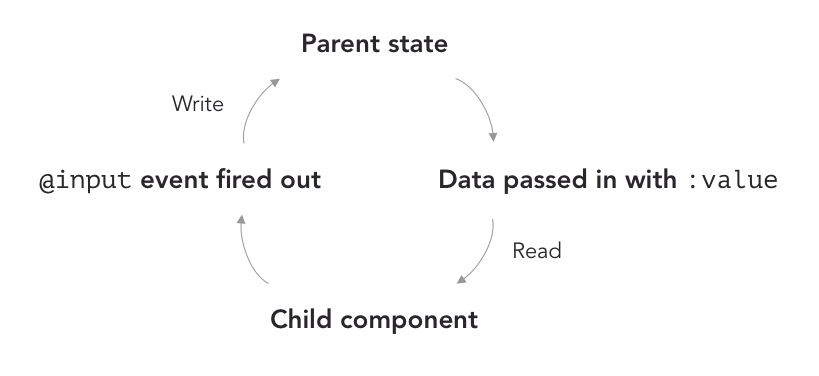

Vue takes it one step further with v-model. It’s a standardised way of controlling component state that works great with form inputs, and third-party dependencies. The concept is based around ‘two-way data binding’. A piece of stateful data is stored on a parent component and passed into a child component (let’s say it’s an input field) with a :value prop. When the input changes, it fires out an input event with the new value. We can listen to that in the parent, and update the parent state.

This approach means the child never actually stores any state; it reflects whatever is passed in, and lets you know if anything’s changed. This model is really powerful, and shouldn’t be underestimated. It forces us to write ‘stupid components’ that end up being far more powerful and reusable than any complex, logic-heavy counterpart. Whenever possible, make components a reflection of state, not stateful.

v-model wraps this all up into a tidy directive - check out the official documentation for detailed instructions. Although often associated with inputs, v-model can be used with any component. As long as you accept a :value prop, and emit an input event, anyone consuming the component can use the v-model directive!

It’s a great example of when to use syntax sugar. Under the hood, v-model is just adding the :value and @input props (plus a bit of cross-browser goodness), but it makes component consumption so much nicer, and more consistent. Having standards and rules might sound draconian, but it’s generally for the good of the developers consuming the code.

It also reaffirms that it’s well worth reading and understanding framework documentation before embarking on a project. Most problems we face have been solved before, and the solutions are often baked into the frameworks already.

Slots and render props

As mentioned earlier, a good component should be extensible and flexible. Along with props, slots (Vue) and render props (React) are a great way of achieving this. I’ll focus mostly on slots to keep things concise, but the same rules apply to render props.

The default slot is often the most overlooked in Vue. One of the great joys of Vue is the HTML-like syntax, but so regularly it gets substituted for yet another prop. Aim to be ‘HTML-like’ when you can; it keeps down that barrier to entry, and improves readability.

// 🤔

<my-button label="Label" />

// 😎

<my-button>Label</my-button>

Slots allow you to override or extend parts of components, but they’re also a way of lifting child logic and methods back up into the parent. I recently wrote an extensive run-through of slots and how to use them, so I won’t dwell on them for too long.

The key takeaway is to document slots, and particularly the scoped data/methods they expose. By placing a method in a scoped slot, you’re extending the public API of the component. It should therefore be as well considered, documented and consisted as your primary props and events.

Avoid flooding slots with all the methods & data from the child component, it may seem like a simple way to cover all bases, but it commits you to maintaining that whole data contract for life. Our aim at all times is to keep the scope of any data contract as tiny as possible.

Refs

Refs are another way of gaining access to a child component from the parent. But unlike all the aforementioned features, refs are dictated by the parent, not the child. This makes them particularly difficult to tie-down and mitigate against. They break the concept of ‘props in, events out’, gaining you access to internal methods and letting you fire ‘events in’. For that reason, they should really be a last resort. But should you need to use them, here’s a few thoughts.

Objects and classes don’t have public/private methods in JavaScript (yet?!), so you can’t explicitly denote a method as being externally reachable, nor hidden. A starting point is to add a sizeable comment above the method declaration, warning future developers that this methods is called externally. If someone refactors later, they’ll know to check the external dependencies too.

methods: {

/**

* Public method

*

* This method is called via refs from outside this component

*/

focus() {

this.$refs.input.focus();

}

}

I’d also err on adding a ‘Public methods’ section to the component documentation summary. Our aim should be to surface every feature, and anything out of the ordinary within the component.

Documentation is as much a way to show how a component should and shouldn’t be used, as it is a feature list preventing future developers unnecessarily building similar functionality.

Summing up

Here’s the tldr;

- Lay out a consistent public API and stick to it

- Document the whys and why nots

- Create extendable base components with mixins and BEM

- Emit standardised events

- Be a reflection of state, not stateful

- Avoid saturating props and scoped slots, keep a tiny data contract

- Be HTML-like

- Document refs, and any public methods

There’s so much that could be expanded on for component contracts. Much of these concepts have come from years of trial & error, and iteration. As you work on even a few projects, you’ll quickly see where the cracks in your system are, and begin to come up with ways to solve them. Note all problems down the minute you encounter of them. It’s far too easy to get to the end of a long project and forget the challenges you faced along the way.

Posted on in Web